Children of the World |

Musings about the Works of Karl Werner-Kueffel Berlin, May 2007

Nearly all of the major world religions include childhood stories of their respective savior in their holy books. Whether as a foundling in a basket rescued from the River Nile or singled out by a birth shrouded in mystery, they arrive through inexplicable divine providence. Even as children, they understand our worries and fears. They preach of a world more just, teach us brotherly love and peacefulness. They are prophets that lead mankind into a better future.

It is through children that we adults catch a glimpse of the peace we lost: “Flowers and children give us an idea of paradise,” Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) wrote around 1300. At first, the saviors and peacemakers are children who teach the adults wisdom, and show them a way full of justice, love and dignity. In numerous cultures around the world, these holy children are a subject of adoration and as a result a subject of depiction in art.

The Western world has examples of the Holy Infant in scenes from the birth of Christ dating from the 4th century. From the 5th century on, he is shown on the lap of his mother Mary. But he is commonly depicted as the new ruler of the world, taking over the role of an adult and judge. It is much later, on 12th and 13th century altarpieces in Central Italy, that Jesus is shown as a young child enjoying his mother’s caress, or as a helpless infant. Childhood, in particular childishness, was not a topic the Christian church dealt with back then.

Very few stories about children from the gospel have found their way into art: apart from the depiction of the birth of Christ, the Massacre of the Innocents and the scene from the Gospel of Mark where Jesus declares “Let the children come to me, do not hinder them; for to such belongs the kingdom.” Between the two extremes of the sermon and the mass murder, the instructive words and the cruel deed, Christian art was inspired to depict infants and children.

Looking at secular art, until the late Middle Ages there are few young children shown, nor is childhood as a stage in life considered worthy of depiction. While children can be found in some scenes, they are treated as small adults, participating in everyday life in their village or town by simply being there.

It is in the early modern era when genre paintings of village or pub scenes portray the life of children at home, working on the fields or simply playing. These village and family scenes are predominant in Dutch paintings, where on the one hand, farmers’ children reflect a village community apparently focused on booze and brawls, the “loose society,” while on the other hand children appear as a symbol of pride and family tradition in the bourgeois society. From the 17th century on, they are shown as swaddled infants on portraits of representatives of the bourgeoisie , or as heirs in the arms of their proud fathers. On the huge family portraits of the nobility, they remain small adults. Here, they represent the continuation of a family dynasty and its power.

The “discovery” of childhood as a stage in life does not happen until the early Enlightenment in the mid 18th century. The new educational theory has an effect on the depiction of children in art as well. Until then, the notion prevailed that children were born with all their skills and specific characteristics just as God made them. Now, the realization that education builds character and that teaching increases knowledge and skills leads to a new image of humanity, and new ideals in education.

The originality, the immediacy to all things, the behavior not yet acquired or enforced by society – John Locke called the spirit of a newborn a tabula rasa in the mid 17th century, a blank slate – all of this puts young children close to the lost paradise, according to early Romanticism. The childlike belief in miracles and the undisguised view of the world turned children in art and literature at the beginning of the 19th century into a mediator between God and the adult world.

From the late 18th century on, people are aware of the importance of childhood development in regards to the shaping of character, learning capabilities and the “development of the heart”. The newborn is no longer considered a universe in itself, but rather a changeable being that can be subjected to practical, spiritual and emotional teachings. Pedagogical science around 1800 is enthusiastic about using education to create free human beings. This was triggered by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s coming-of-age novel “Emile, or On Education” (1762) which pleaded the case for leaving children to their own natural devices and raising them away from the influences of civilization, as they are closest to the natural state. Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1927) advocated the promotion of children in moral, spiritual and practical aspects. This integrated approach dominates the basic education philosophy into the 20th century and strengthens children’s rights to be educated and to be allowed to learn.

Of course, the reality of everyday life of children, and the protection of their rights by the adults, looked quite different for most of the population until the late 19th century. A high infant mortality rate due to unsanitary conditions, childhood diseases for which there was no cure, malnutrition, lack of education, physical exhaustion from working at a young age, punishments and beatings: that is what childhood looked like. The protection of children and young people does not become a general obligation by society until that society’s prosperity is measured by the health and skills of the next generation. Facilities for health care and children’s education are key factors for a successful national economy.

A hundred years ago, Ellen Key (1849-1926) ventured the following prognosis: “The 20th century might become the century of the child.” She made this remark during a period when youth just started to discover and develop its own culture and dynamic. The term “youth” demands to become a program for magazines, for a new style in art, for a new awareness of life. The valuation of youth, its right to childhood and self-determination, manifests itself in numerous newly coined words: youth movement, youth hostel, youth protection, Children and Young Persons Act, and many others. The state realizes that its young people deserve protection and begins to discover them both as small citizens and a political factor. It is not without self-interest that the new countries of the 20th century make use of the dynamic and idealism of youth in order to reshape the nation. In its most extreme form, dictatorships abuse them as complacent victims and perpetrators in a radical change of society.

In many ways, Ellen Key’s prognosis came true. The 20th century was a century of children and youth. They received more support and protection than during any other era. But it also abused them for ideological warfare in more despicable ways than any other century. Looking at one ideal of the Enlightenment movement, the education of young people to create “free humankind,” the last century in particular offers numerous examples of delusion and abuse.

The creative arts accompany this contradictory process of supporting and abusing children in countless motifs in paintings, graphics and photography. These pictures not only measure social conflicts, they also demonstrate that children are not one inch closer to paradise than adults. No sooner than they are born, children, supposedly symbols of salvation, future and sustainability, enter the conflicted world of adults. At the turn of the millennium, Neil Postman (1931-2003) stated that “childhood is vanishing.” He considered childhood a construction of the bourgeois information society beginning in the 16th century and felt it was disappearing into the modern communication societies.

During the past 200 years, democratic countries have expanded their laws designed to protect children and young people. That is the good news. Nonetheless, children and young people remain the first casualties and victims of natural catastrophes, flights from their homes, forced displacements, epidemics and warfare. Their necessary area of protection is the first to be sacrificed, unwittingly and recklessly. Their right to health and education, to physical and spiritual integrity, to family and community, remains more than ever a worldwide calling.

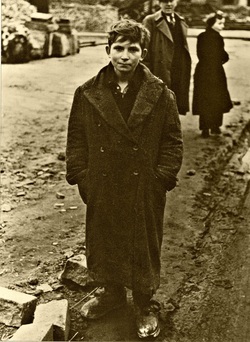

With his work in 21 pieces, artist Karl Werner-Kueffel takes a look at different situations that children of the world face. His picture cycle reaches a depressing conclusion about he harsh reality of the life of children, our next generation. Epidemics, emotional neglect, famine, wartime atrocities, abuse – it is an inferno that attacks these children, causing them to doubt the world and to fail in it. “Children of the World” does not show paradise but hell on earth. There are only a few scenes in which his children experience moments of support, love, security. These few pictures give hope to mankind and offer the world an emotional sense in their religious communities, in brotherly love and affection.

The works of Werner-Kueffel are intended not so much as a piece of art, but rather as an intense appeal to do something for these violated children in order to save our future. “Children are the future – but they need our help here and now in order to have a perspective for the future in the first place,” the President of the SOS Kinderdoerfer charity, Helmut Kutin, wrote recently. The picture cycle is such a SOS call through the medium of art. My wish for this book is that it may inspire many people to become advocates for the children of the world who have no future. I hope that viewers will not just look at the artist’s work, but also feel inspired by these heartbreaking images to approach those courageous organizations which have been working for decades towards creating a future for our children.

It is through children that we adults catch a glimpse of the peace we lost: “Flowers and children give us an idea of paradise,” Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) wrote around 1300. At first, the saviors and peacemakers are children who teach the adults wisdom, and show them a way full of justice, love and dignity. In numerous cultures around the world, these holy children are a subject of adoration and as a result a subject of depiction in art.

The Western world has examples of the Holy Infant in scenes from the birth of Christ dating from the 4th century. From the 5th century on, he is shown on the lap of his mother Mary. But he is commonly depicted as the new ruler of the world, taking over the role of an adult and judge. It is much later, on 12th and 13th century altarpieces in Central Italy, that Jesus is shown as a young child enjoying his mother’s caress, or as a helpless infant. Childhood, in particular childishness, was not a topic the Christian church dealt with back then.

Very few stories about children from the gospel have found their way into art: apart from the depiction of the birth of Christ, the Massacre of the Innocents and the scene from the Gospel of Mark where Jesus declares “Let the children come to me, do not hinder them; for to such belongs the kingdom.” Between the two extremes of the sermon and the mass murder, the instructive words and the cruel deed, Christian art was inspired to depict infants and children.

Looking at secular art, until the late Middle Ages there are few young children shown, nor is childhood as a stage in life considered worthy of depiction. While children can be found in some scenes, they are treated as small adults, participating in everyday life in their village or town by simply being there.

It is in the early modern era when genre paintings of village or pub scenes portray the life of children at home, working on the fields or simply playing. These village and family scenes are predominant in Dutch paintings, where on the one hand, farmers’ children reflect a village community apparently focused on booze and brawls, the “loose society,” while on the other hand children appear as a symbol of pride and family tradition in the bourgeois society. From the 17th century on, they are shown as swaddled infants on portraits of representatives of the bourgeoisie , or as heirs in the arms of their proud fathers. On the huge family portraits of the nobility, they remain small adults. Here, they represent the continuation of a family dynasty and its power.

The “discovery” of childhood as a stage in life does not happen until the early Enlightenment in the mid 18th century. The new educational theory has an effect on the depiction of children in art as well. Until then, the notion prevailed that children were born with all their skills and specific characteristics just as God made them. Now, the realization that education builds character and that teaching increases knowledge and skills leads to a new image of humanity, and new ideals in education.

The originality, the immediacy to all things, the behavior not yet acquired or enforced by society – John Locke called the spirit of a newborn a tabula rasa in the mid 17th century, a blank slate – all of this puts young children close to the lost paradise, according to early Romanticism. The childlike belief in miracles and the undisguised view of the world turned children in art and literature at the beginning of the 19th century into a mediator between God and the adult world.

From the late 18th century on, people are aware of the importance of childhood development in regards to the shaping of character, learning capabilities and the “development of the heart”. The newborn is no longer considered a universe in itself, but rather a changeable being that can be subjected to practical, spiritual and emotional teachings. Pedagogical science around 1800 is enthusiastic about using education to create free human beings. This was triggered by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s coming-of-age novel “Emile, or On Education” (1762) which pleaded the case for leaving children to their own natural devices and raising them away from the influences of civilization, as they are closest to the natural state. Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1927) advocated the promotion of children in moral, spiritual and practical aspects. This integrated approach dominates the basic education philosophy into the 20th century and strengthens children’s rights to be educated and to be allowed to learn.

Of course, the reality of everyday life of children, and the protection of their rights by the adults, looked quite different for most of the population until the late 19th century. A high infant mortality rate due to unsanitary conditions, childhood diseases for which there was no cure, malnutrition, lack of education, physical exhaustion from working at a young age, punishments and beatings: that is what childhood looked like. The protection of children and young people does not become a general obligation by society until that society’s prosperity is measured by the health and skills of the next generation. Facilities for health care and children’s education are key factors for a successful national economy.

A hundred years ago, Ellen Key (1849-1926) ventured the following prognosis: “The 20th century might become the century of the child.” She made this remark during a period when youth just started to discover and develop its own culture and dynamic. The term “youth” demands to become a program for magazines, for a new style in art, for a new awareness of life. The valuation of youth, its right to childhood and self-determination, manifests itself in numerous newly coined words: youth movement, youth hostel, youth protection, Children and Young Persons Act, and many others. The state realizes that its young people deserve protection and begins to discover them both as small citizens and a political factor. It is not without self-interest that the new countries of the 20th century make use of the dynamic and idealism of youth in order to reshape the nation. In its most extreme form, dictatorships abuse them as complacent victims and perpetrators in a radical change of society.

In many ways, Ellen Key’s prognosis came true. The 20th century was a century of children and youth. They received more support and protection than during any other era. But it also abused them for ideological warfare in more despicable ways than any other century. Looking at one ideal of the Enlightenment movement, the education of young people to create “free humankind,” the last century in particular offers numerous examples of delusion and abuse.

The creative arts accompany this contradictory process of supporting and abusing children in countless motifs in paintings, graphics and photography. These pictures not only measure social conflicts, they also demonstrate that children are not one inch closer to paradise than adults. No sooner than they are born, children, supposedly symbols of salvation, future and sustainability, enter the conflicted world of adults. At the turn of the millennium, Neil Postman (1931-2003) stated that “childhood is vanishing.” He considered childhood a construction of the bourgeois information society beginning in the 16th century and felt it was disappearing into the modern communication societies.

During the past 200 years, democratic countries have expanded their laws designed to protect children and young people. That is the good news. Nonetheless, children and young people remain the first casualties and victims of natural catastrophes, flights from their homes, forced displacements, epidemics and warfare. Their necessary area of protection is the first to be sacrificed, unwittingly and recklessly. Their right to health and education, to physical and spiritual integrity, to family and community, remains more than ever a worldwide calling.

With his work in 21 pieces, artist Karl Werner-Kueffel takes a look at different situations that children of the world face. His picture cycle reaches a depressing conclusion about he harsh reality of the life of children, our next generation. Epidemics, emotional neglect, famine, wartime atrocities, abuse – it is an inferno that attacks these children, causing them to doubt the world and to fail in it. “Children of the World” does not show paradise but hell on earth. There are only a few scenes in which his children experience moments of support, love, security. These few pictures give hope to mankind and offer the world an emotional sense in their religious communities, in brotherly love and affection.

The works of Werner-Kueffel are intended not so much as a piece of art, but rather as an intense appeal to do something for these violated children in order to save our future. “Children are the future – but they need our help here and now in order to have a perspective for the future in the first place,” the President of the SOS Kinderdoerfer charity, Helmut Kutin, wrote recently. The picture cycle is such a SOS call through the medium of art. My wish for this book is that it may inspire many people to become advocates for the children of the world who have no future. I hope that viewers will not just look at the artist’s work, but also feel inspired by these heartbreaking images to approach those courageous organizations which have been working for decades towards creating a future for our children.